“Growing up in a family living in poverty or near poverty negatively impacts a child’s health throughout his or her life,” according to NCChild’s 2014 Child Health Report Card. In the same report it also says that “education and health outcomes are also tightly intertwined; success in school and the number of years of schooling impact health across the lifespan.”

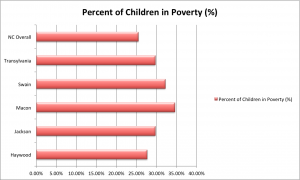

25.5 percent of children in North Carolina lived in poverty in 2014. Western North Carolina’s rates are higher than the state rate, according to the Kids Count Data Center, a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

The Kids Count Data Center’s goal is to track the wellbeing of children in the United States using high-quality data and trend analysis. Their national headquarters uses 50 state centers in order to collect local data.

North Carolina’s data is collected through NCChild, formerly known as “Action for Children North Carolina,” which is located in Raleigh, NC.

Nearly 30 percent of children in Jackson County are under the poverty line.

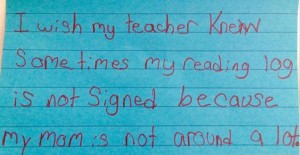

This is only one of the photos of the #IWishMyTeacherKnew assignment, reading “I wish my teacher knew sometimes my reading log is not signed because my mom is not around a lot.”

Photo by Kyle Schwartz

A teacher at Jackson County Cullowhee Valley School (CVS) who wanted to stay anonymous, sees the effects of these levels of poverty on her students every day.

“Some administrators and politicians outside of the classroom will tell you that socioeconomic status doesn’t matter. I agree that it doesn’t mean that you don’t provide the same opportunities, but it does have a direct effect on student performance. …They’re not being read to at home, and it’s not because the parents choose not to. They’re working like two, three jobs. They’re working their butts off… There’s no way that that can be a level playing field.”

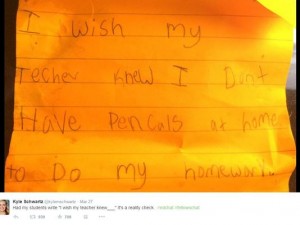

Even the students know when things are not going the way that they should at home. This can be seen in Denver, Colo. teacher Kyle Schwartz’s #IWishMyTeacherKnew assignment.

This assignment caught the nation’s attention, and just goes to show more extensively that every student has something to struggle with, whether it’s a learning disability, being lonely or feeling like they’re unable to do their schoolwork because of problems at home.

Another of Kyle Schwartz’s students #IWishMyTeacherKnew note saying “I wish my techer knew I don’t have pencals at home to do my homework.”

Photo by Kyle Schwartz

The CVS teacher agreed that problems at home, such as poverty, “absolutely” cause extra troubles at school.

“As a human being, if you have something else you’re worried about, you can’t focus on something as abstract as learning, you know? If your basic needs aren’t met, learning is secondary.”

Jonathan Mark Harris, a teacher’s assistant at CVS agreed, saying, “When there’s less money, there’s more anger in the home, when there’s more anger in the home, there’s less sleeping in the child, there’s less comfortable eating, everything’s different.”

The effects of poverty were also seen in the 2015 working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which compared the adults who were exposed to different types of school finance reforms based on their place and year of birth.

Their study, which is behind a paywall, found that a 10 percent increase in spending per student from kindergarten through twelth grade overall meant “0.27 more completed years of education, 7.25 percent higher wages, and a 3.67 percentage-point reduction in the annual incidence of adult poverty.” Their study also noted that the effects were much more pronounced in low-income children.

According to their abstract, “spending increases were associated with sizable improvements in measured school quality, including reductions in student-to-teacher ratios, increases in teacher salaries, and longer school years.”

Per-student spending in North Carolina has been cut by 14.5 percent since 2008, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which equals out to about $855 less spent per student. CBPP believes this is because states are still trying to recover from the recession that began then.

One of the ways that North Carolina schools try to combat the link between poverty and education is by giving Title I status to schools that have students who are the most at risk for failure. Title I funding comes from the No Child Left Behind program, which is a controversial program due to their concentration on testing, but the funding is shown to help.

In order for a school to be considered a Title I school, needs to have 35% of its students qualify for the federal free/reduced lunch program.

Terri Hollifield, Title I Director for Jackson County Schools, said that all of the schools in Jackson County qualify for Title I funding. The only schools in Jackson County that are using their Title I status are Blue Ridge, Cullowhee Valley, Scott’s Creek and Smoky Mountain Elementary because the county believes, based on research, that it is more effective to meet those needs earlier in the education process.

According to Hollifeld, the money that comes from being considered a Title I school in Jackson County is used “to reduce class sizes, to hire additional teachers for a classroom.”

“However, if you look at our schools that do not receive Title I funding, they have about the same student-teacher ratio, so we’re using that federal money in order to hire additional personnel, but we’re also making sure that it’s spread out so that there’s comparable services across the system,” said Hollifeld. Hollifeld believes that this is working for the county right now.

Cutting class sizes has been proven to help low income students learn, especially in the early years of their education, because more time spent with each student makes for a better education for that student.

The percentage of students in each school in Jackson County can be seen in the fusion table below. Schools with less than 50 percent of students below the poverty level are marked with yellow circles. Schools with more than 50 percent of students below poverty level are marked with green circles.

Dr. Michael Murray, Superintendent of Jackson County Public Schools, said that he thinks that poverty should be something taken into account when you look at the test scores for Jackson County Schools.

“Multiple factors should be represented with a stronger emphasis on actual growth and using genuine assessment instead of a high stakes on size fits all score that is really not relevant to the learning that is going on daily within our organization. Multiple factors such as graduation rate, socioeconomics, rates of poverty, numbers of free and reduced lunch children, and many other factors need to be taken into account if you are going to try and measure an individual school or school systems effectiveness,” said Murray in an email message.

However, when you see that federal spending has been cut by 10% since 2010, according to CBPP, from $17.2 billion to $15.6 billion nationwide, it might make you wonder what that means for the children attending these schools.

Some students struggle when there school isn’t in session. Even when there is, they will occasionally rely on teachers to help them look and act like their peers, particularly in the younger grades.

“They know that they have needs that are different than other students, especially the more unkempt ones, they know. They’ll come to us and say ‘Will you brush my hair?’ and not because they see other kids doing it, but because they know it’s a need that can’t be met at home for whatever reason,” said the current CVS teacher.

Annie Kitchin, a former Cullowhee Valley School teacher doesn’t blame the schools for failing the children.

“I think the biggest failing isn’t in the schools. I would point that finger directly at the state and the legislators who continually cut funding and create programs and laws that aren’t supportive of the classroom, the teachers or the students. I used to spend money from my own pocket all of the time to buy things for my classroom that funding couldn’t provide, and a child’s parents couldn’t afford. I don’t know of a single teacher who hasn’t spent their own money to support their students because the state, or local funding wasn’t available. It’s tough to write a grant every time you need to buy crackers because 1/4 of your students are starving and don’t have snacks at home, or you need to buy pencil grips for a student who is struggling to hold their pencil correctly. Those things add up over time, and without them that child is at an extreme disadvantage.”

The Sylva Herald reported on May 27, 2015 that the Jackson County School Board approved a new policy that states that any child at Smoky Mountain Elementary School, the Jackson County School of Alternatives, the Blue Ridge School and Blue Ridge Early College will be able to eat a free lunch without being required to submit paperwork and feel singled out by the school system. This policy will be in effect for up to the next four years, but will be watched to make sure that the county isn’t losing money from this policy.