It was a situation out of nearly every woman’s nightmares. On a Saturday morning, in mid-October of 2019, a female Western Carolina student (whom we will call “Anne” for privacy reasons) broke up with her boyfriend. His response spiraled into something that would cause panic throughout her entire household.

“Anne” and her roommates lived in the Summit, an off-campus housing apartment complex. Photo taken from the Summit’s website.

The boyfriend had slept over at Anne’s apartment and after being broken up with in the morning, he had threatened to kill himself.

Like many college-aged girls, the students did not know what to do in light of such a serious threat. Anne initially did not want to call the police on her ex-boyfriend and instead insisted that they call Western Carolina University’s Counseling & Psychological Services (CAPS) to ask for help.

“I was immediately referred to a [the crisis clinician]. I never really got the name of who was supposed to help us through the crisis. He said he was going to have to call the police, and I understood that,” said Anne’s roommate, whom I will call “Michelle” for privacy reasons. “He didn’t really give us much advice after that.”

However, neither of the resources were able to help them for two simple reasons:

One, it was a weekend, and CAPS only operates in full on weekdays. According to the CAPS website, the CAPS office is open Monday to Friday from 8 am to 5 pm, and those seeking help after hours or on weekends must call the crisis clinician (this was the person Michelle called).

Two, they were living just across the street from WCU’s Cullowhee campus. Despite the fact that the boyfriend himself lived on campus, he had made threats to kill himself in his girlfriend’s off-campus apartment which makes it out of Campus Police’s jurisdiction.

“We could see campus police doing their patrols [on campus] from, like, our apartment, and they wouldn’t come and help,” said Anne.

The girls claim it took nearly an hour and a half for Jackson County Police to arrive on the scene. The ex-boyfriend in question was committed to a hospital for a few days, and when he returned to school, he demanded an apology from Anne.

“All my roommates came together to help me cut ties with him, and . . . I guess he didn’t think that we were treating him fairly and that we weren’t listening to him, or whatever,” said Anne.“So, he wanted me to apologize for calling the police on him. He described his time in the hospital as, like, really terrible and he wished he [didn’t have to go to the hospital]. Like [. . .] I’m sorry, I didn’t know it would be that way, but at the same time, I won’t apologize.”

When all was said and done, Anne sought a restraining order against her ex-boyfriend. Since their living conditions forced them to wait for the Jackson County Police to take action, the girls felt as though they were left dead in the water.

“If it were, like, a more serious situation, like, with an active person trying to kill himself or somebody else, it would’ve been too late,” said Anne.

Sergeant Brittany Thompson, a Public Safety Supervisor at the WCU University Police, says that the Jackson County Police’s slow response time may be due to them being understaffed. Fully staffed, Jackson County Police and University Police have roughly

WCU alumna Detective Brittany Thompson outside of the WCU Police Department. Picture by Sydni Hall

the same number of officers, however, the Jackson County Police covers nearly 500 square miles of territory, whereas University Police only cover a mile.

That mile of jurisdiction is what prevented the University Police Department from intervening in the situation. However, Thompson encourages off-campus students to still call whenever they are dealing with a situation.

“Every situation is different and must be assessed accordingly. One of the first things that would need to happen is a law enforcement agency would need to be notified,” said Thompson. “All agencies have the ability of doing welfare checks on individuals threatening self-harm in their jurisdiction. If an officer determines that there is probable cause that a crime has occurred, an arrest shall be made. If no probable cause exists, an officer may refer a victim to the Magistrate’s Office to take out charges.”

Michelle and her roommates may have made a mistake by limiting themselves to only two of the resources the campus offers. While relationship concerns are one of the main reasons that students seek CAPS’ services, according to CAPS Director Dr. Kim Gorman, they are not the primary ones.

“The main reasons students come to CAPS is for depression and anxiety symptoms,” said Gorman.

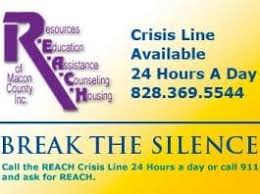

Resources Education Assistance Council Housing (REACH) is an organization partnering with CAPS that specializes in domestic abuse and violence resources. REACH provides support services for any individual who has been victimized or experienced trauma as a result of domestic or sexual violence, including human trafficking. According to REACH’s Assistant Director Jennifer

A flier created by REACH displaying its crisis line

Turner-Lynn, REACH served 622 Domestic violence, 249 sexual assault, and 48 human trafficking victims/survivors in the 2018-2019 fiscal year. Unlike CAPS, REACH is not limited to on-campus victims.

“Trauma [from an abusive relationship] can have both short and long-term impacts including physical, physiological, and mental health consequences,” said Turner-Lynn in an email. “Individuals can reach our 24-hour crisis hotline to speak with someone who can either provide immediate information, safety planning, or make a referral.”

REACH perhaps would have been able to offer the girls more specific advice to their situation, which according to Turner-Lynn, is a fairly common abusive attempt at maintaining control. REACH, CAPS, and Campus Police can offer counseling; only Jackson County Police could only offer any chance of diffusing the situation, and them being understaffed with a much too large jurisdiction resulted in Michelle and her roommates having to wait an hour for a response.

The solution is unclear. Do we hire more police officers, or expand the jurisdiction of campus police to include off-campus students? Anne and her roommates aren’t claiming to know.

“I mean, I don’t know what he was capable of,” said Anne. “So, I was nervous that he was more so a threat to himself, but he could’ve . . . like, [he could have] came for us, as well.”