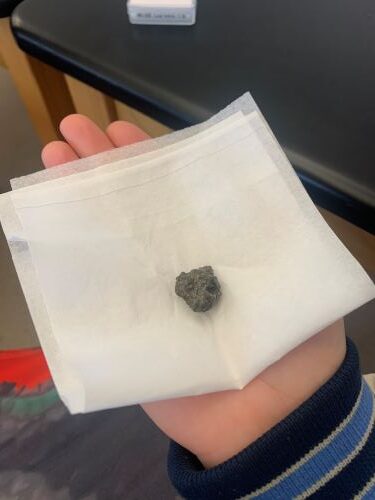

I never thought that as a journalist I would be able to hold a 4 billion year old rock in the palm of my hands. This meteorite is one of many in Dr. Amy Fagan’s collection.

Fagan is an associate professor of geology at WCU and the chair of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group for NASA (LEAG) studying lunar meteorites to find out more information about the moon’s surface and its chemical composition.

Fagan’s interest in lunar geology happened in graduate school when she had to make some quick decisions on the focus of her research. Originally she wanted to work in planetary research because of a class she took on the extinction of dinosaurs which led to an interest in impact craters.

“It was kind of by accident. It was not what I had planned at all,” Fagan said. “My advisor left halfway through my degree and I had to make a pretty last minute switch. Like 180 switch to not what I was intending on doing for grad school and for my career. It’s the best thing that could have happened to my career.”

Her Ph.D. advisor at the University of Notre Dame was the chairman of LEAG at the time. Since Fagan already has some connections to work with NASA, she was able to get onto the executive committee and be elected as the chairman in 2020.

Most of what Fagan studies is Apollo rock samples that were brought back from the moon from 1969 to 1972. She also studies lunar meteorites.

The difference between the Apollo rocks and the lunar meteorites is the location where they are found. The Apollo rocks are from the near equatorial region of the moon, and the near side of the moon is what faces Earth. Lunar meteorites can vary in location all over the moon.

Fagan uses the chemical composition of these meteorites to figure out the location of where they came from then compares the results to the Apollo rocks, rock that is not from the moon, and tries to learn more about the moon’s history.

“We have a lot of knowledge about the moon. There is a lot of places in the solar system that we really have barely scratched the surface,” Fagan said. “We have the return samples from the moon. We know where they were collected. We have a lot of orbital assets around the moon. So we have a lot of information about the surface of the moon. We even have gravity measurements of the moon so we kind of know what the interior is like.”

The main way that Fagan studies these meteorites are by looking at the chemical composition through a microscope. She uses a slice of a lunar meteorite that is around 30 microns thick. For comparison, a piece of paper is about 100 microns thick.

Under the microscope, Fagan looks at the minerals in the meteorites to see what crystallized fast and what didn’t. The use of the microscope also helps identify chemicals or rocks that are on the moon that are also found on Earth.

One of the most fascinating things that comes from Fagan’s studies of meteorites is that Earth has a lot of rocks that includes a similar chemical composition to lunar meteorites. Because of earth’s plate tectonics, a lot of Earth’s history has been erased, and studying the moon has given us a better idea of not only the moon’s history but Earth’s as well.

This means that since the moon and Earth are so close together, they got hit with the same chemicals which is a reason why we have the same rocks like Basalt and Troctolite that can be found on Earth and the moon.

For Fagan’s geology classes she brings her knowledge of the moon in by discussing what rocks and materials are on the moon and on Earth.

“Basalt is a volcanic rock, like what we have from Hawaii. If you look up at the night sky at a full moon, the black splotches on the moon, that’s basalt,” Fagan said.

Her solar system class takes a whole week just to talk about the moon. She wants her students to be fascinated by what the scientists have discovered on the moon, and the unknown that still needs to be uncovered.

“I want them to feel in awe of space and how cool it is,” Fagan said.