Western Carolina students are crafting happy hour into the hoppy semester with the evaluation and experimentation of homebrewing in class.

Sean O’Connell, microbiology professor and mentor at WCU for 21 years, is teaching students the process of crafting their own beers, ales, malts, and more. Students were put to the test by crafting their own brews during the year.

“It bridges the gap between science and everyday stuff. Understanding the chemical processes behind drinks and food,” Lorien Helm, a biology major at WCU, said during the WCJ visit to the class in Spring 2022.

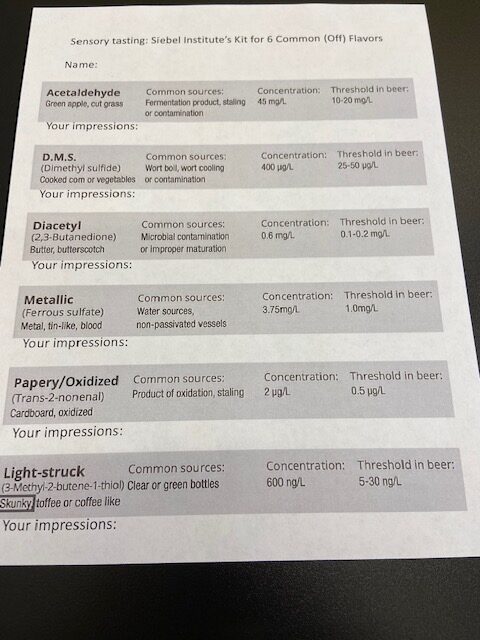

The class of 16 students sat in a U shape around the room with sample cups filled with beer. This particular day was a sensory tasting day to identify what the students tasted and discuss it as a group. It was one of the few times during the semester the entire class was able to share laughs, smiles and disgust all together for the 5-hour lab.

History tells that beer has been made from fermented sugar water for over 10,000 years. Hops, a plant that adds bitterness, have only been used for 500 years. Brewing beer is nothing new, but the understanding of beer is something new for students in the class.

Let’s start brewing

Homebrewing has only four main ingredients: water, barley, hops, and yeast. Using only those ingredients, students brew mead, wine, ciders and beer during the semester and learn a ton of chemistry and biology.

Water is different everywhere and impacts the brew. The same goes for the types of crops used. The same recipe could be used in four areas of the world, but all will taste different because of the different waters and crops.

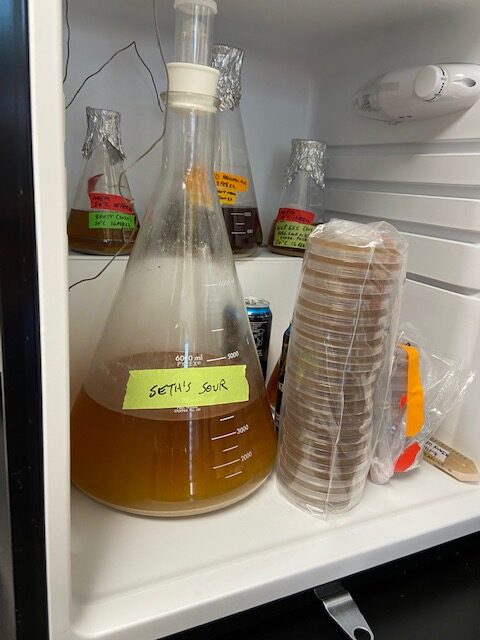

The process of homebrewing starts with the making of a yeast culture. This occurs before the chaos of brew day. One can determine if yeast is good to go in a beer by putting it under a microscope.

The yeast goes in last and determines the style of beer. The yeast can ferment for a few days or weeks and become ales, or ferment for months and make a lager.

“You can have the perfect recipe, but if your yeast is not up to specks and can’t ferment properly, you’re gonna make a bad beer,” O’Connell said.

Brew days consist of weighing out grains, barley, or malt. Grains must be crushed and cut open to release the starches inside.

With every step of brewing, students had to clean before going to the next step. O’Connell’s microbiology background enforces the importance of cleaning. Cleaning gets all of the particles off. After cleaning, the students disinfect the area using bleach or a chemical that sterilizes the area or tools. If only sterilized, the tool is still dirty with extra microbes that can affect the flavor of the beer.

Once done, the grains are mashed and boiled. Mashing activates enzymes. The enzymes then break the starches from the grains into smaller sugars, turning the water into sugar water. The mashing and boiling take about an hour each.

The students use an all-in-one brewing system that plugs into the wall, boils everything, and cools it down.

The grains are removed from the water and the water is boiled again to kill any microbes or things that may cause unwanted flavors to the beer.

“Changing small aspects can change the whole outcome and that’s very concerning sometimes ’cause you can make a small mistake and ruin the entire batch,” Morgan Barnes, chemistry major and math minor, said.

Hops are added to mix bitterness with the sweetness from the sugar water. The boiling of the oils from the hops plant brings the bitter compounds out of the plant and into the water.

“Every beer you can buy is really a balance between the sweetness from the sugar in worts (liquid from the mashing) that you’ve produced and the bitterness from the hops,” O’Connell explains.

What is important to know about the life of a homebrew

The style of the beer determines the expiration of the brews. Barley wine can last up to 20 years as long as there is a good seal, like wax, to keep oxygen out. O’Connell shared how he has brewed something for each of his daughters, one being his favorite, barley wine.

Light, temperature, and oxygen can ruin a brew. When light hits the hops in a beer, it can cause a “skunky” taste. Temperature can also affect taste. The best taste for a beer comes from staying cold, out of sunlight and properly sealed.

As an experiment, the class tried making a pressurized lager. They put a lager recipe in a keg and had it ferment in the keg. By keeping the pressure at around 10 pounds per square inch, the yeast will ferment faster at room temperature and change the taste.

The class also performed a dry hop and yeast experiment. The dry hop used four different hops in small containers with the same brew. The yeast experiment had the same pale ale in different containers and each container held different strength yeast.

“You know what it’s supposed to taste like and if it deviates from that, you may not wanna buy it again,” O’Connell said.

Breweries make sure that the customer knows what they are getting because it is always the same. Sensory panels help brewers keep the beer the same taste when made.

O’Connell encourages his students to taste, critique and use their brews for learning, not only for drinking. The purpose of the class is to learn how to evaluate and appreciate different brew styles.

“I want the students to walk out knowing how to brew something if they want to. But more importantly, and this is where Cicerone comes in, how to evaluate that beer cider or wine,” O’Connell said.

Students practiced sensory evaluations. They took commercial beers or went to a brewery and tried a beer as a group. As a group, they taste and look at aromas. There are a couple of thousands of compounds in a beer and each person can taste different ones.

With group sharing comes trust and support. O’Connell shared the importance of a supportive brew community and how they use each other to share ideas on how to make the beer better if they want to try it again. O’Connell had a supportive brew group in college and might have quit brewing if he did not have that support.

With Asheville down the road, students are able to see different job opportunities that they may not realize are there. O’Connell shared how Asheville offers a yeast production facility, experimental hop growing lab, and more. Lab tech positions and quality control jobs are needed heavily in the beer-making industry.

To make it easier for the students who want to go into the brewing industry, students are able to get certificates through Cicerone.

Cicerone trains staff or bartenders to understand beer styles and match beer with food. There are large distinctions between a malty taste, fruity taste, bitter taste and sweet taste. O’Connell is certified through Cicerone.

What is the future of the class?

The class started in 2020 but was disrupted when the coronavirus hit. The class is offered once every two years during the spring semester. The class welcomes all students as long as they turn 21 before the spring break of that year.

Students have successfully made their own unique beers. Of the batch, there is a sour, dragon fruit beer, blackberry ginger cider, mint chocolate stout, mead, a German dark beer called doppelbock and many more. One student challenged themselves to make bitters.

O’Connell anticipates bringing the students’ work out of the classroom. He wants to see their brews being a part of local brewing and be showcased at special events at WCU or conferences on campus with the university’s support.

The small brewing class calls itself the Tuckaseegee Brewing Corporative. If given the opportunity, they would like to keep the energy alive when being showcased as a Western Carolina University-made beer.

The beer that is left over after the class is either sent home with students or professors.

On sensory tasting day, students are to blindly sample each brew and identify the specific tastes. Photo by Savanna Tenenoff

This is the sensory test sheet that the students use to pin-point what they are tasting. Photo by Savanna Tenenoff

Dr. O’Connell and his students are taking a break after sensory tasting. In front of them are the specific glasses used for particular beers. Photo by Savanna Tenenoff

The class calls themselves the Tuckaseegee Brewing Cooperative. They take pride in the name and hope to make it an official small local WCU beer in the future. Photo by Savanna Tenenoff

Students are given a small control beer and saltine to cleanse their taste palate. This allows them to taste and acknowledge more ingredients in the sample beers. Photo by Savanna Tenenoff