As we’ve moved into the 21st century, the harsh realities faced by indigenous communities covered up for generations are brought to light, and the fight for indigenous rights has grown, but not nearly enough. Not yet.

In honor of November being Native American Heritage month, WCU offered various events on campus to help educate while bringing awareness to students, and recognize the university’s connection to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Events included speeches by the creators of the ‘We are Resilient’ podcast, Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle, and the ‘We Will Not Be Silenced: Standing for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’ exhibit in the Bardo Arts Center.

A wide variety of topics were discussed including the possible overturning of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) by the Supreme Court, the effects of Native American generational trauma, and tribal sovereignty. But the primary focus for the month within the university community was the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) epidemic.

According to a report by the National Institute of Justice in 2016, more than 4 in 5 indigenous women have experienced some sort of violence in their lifetimes, 96% described their attacker as non-native. Native American women are also 2.5 times more likely than women of any other race to experience violence, stalking, or sexual assault.

The murder rate is 10 times higher than the national average for women living on reservations, and the third leading cause of death for indigenous women in the United States as reported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

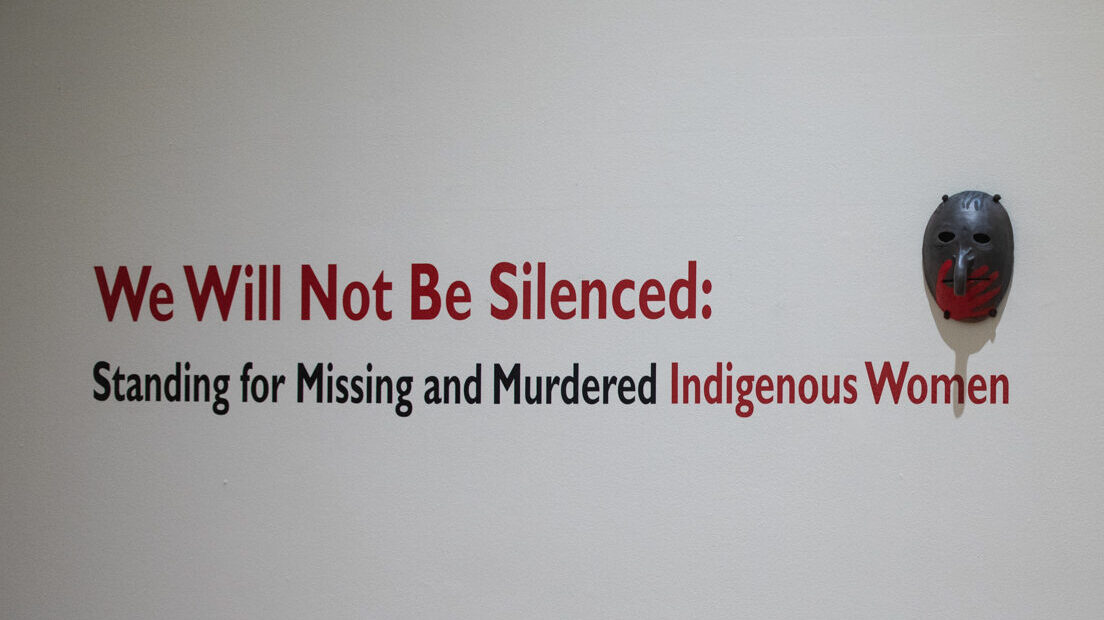

The ‘We Will Not Be Silenced: Standing for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’ Exhibit, organized by Cherokee Center Director, Sky Sampson, was created to honor and recognize the missing and murdered indigenous women throughout the United States and the world.

“I really wanted to bring light to these women and their families. Let people know that they’re not forgotten, and that we see and hear our indigenous families throughout the country,” said Sampson.

Initially, this project was intended to be a small interactive photo gallery in WCU’s Wellness Fair held on Sept. 14. Sampson gathered photographers Ashley Evans (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina) and Dylan Rose (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) to photograph native students and alumni with personal connections to MMIW, dressed in traditional indigenous clothing with red handprints painted over their mouths.

When Sampson reached out to the indigenous WCU community, the response was so positive that the project quickly grew into something bigger. There have been comparable exhibits to aid awareness for the cause focused on tribes in the West, but few have covered the Eastern tribes. Sampson was excited at the opportunity to expand it.

On March 3, 2022 around 50 women and children arrived at the photoshoots at Kituwah (Kih-too-wah) Mound, a sacred location used by the Cherokee people for ceremonies and prayer. Because WCU resides within the ancestral homelands of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, once known as “Two Sparrows Place,” the photos in the exhibit are primarily of Cherokee women. Though members of the Choctaw, Comanche and Coharie tribes were also included.

“It was humbling and an extraordinary honor to use my gift to support this important movement. This project was the most powerful and spiritual experience of my 22-year career as a professional photographer,” said photographer Ashley Evans. “These women came before me in a unified front, with strength and resilience that did not require a single word to be spoken. I heard each and every one of them. My relationship with my indigenous identity and community has grown as a result, and I am forever grateful for this invaluable experience.”

Bearing the red handprint on their faces, the women stood proudly amongst the mountains dressed in the beautiful garments of their culture to be photographed. The handprint symbolizes their acknowledgment that they were once silenced, but refuse to be silenced ever again.

“We choose to stand up and be the voice for the girls that are missing or murdered, but also for females in general. We have our voice back, and we are not going to let it go,” said Sampson.

The photographs, as well as MMIW sculptures, are on display in the Bardo Arts Center until Dec. 9 featuring work by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Comanche Nation, Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, and Métis Nation artists.

But just in case you don’t have time to stop by Bardo before then, there are many other resources to learn about missing or murdered indigenous women. One is even based here in Western North Carolina.

The three Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian creators of the ‘We are Resilient’ podcast Ahli-sha Stephens, Maggie Jackson, and Sheyahshe Littledave has made it their mission to discuss MMIW cases that have been forgotten by law enforcement but not forgotten by families.

The three women run their podcast in their free time while maintaining their full-time jobs to aid the cause and humanize the women whose memories have been dwindled down to ‘missing’ posters. They complete all necessary research independently through the internet and contacting families. Most of their episodes are based upon requests from indigenous people all over the country.

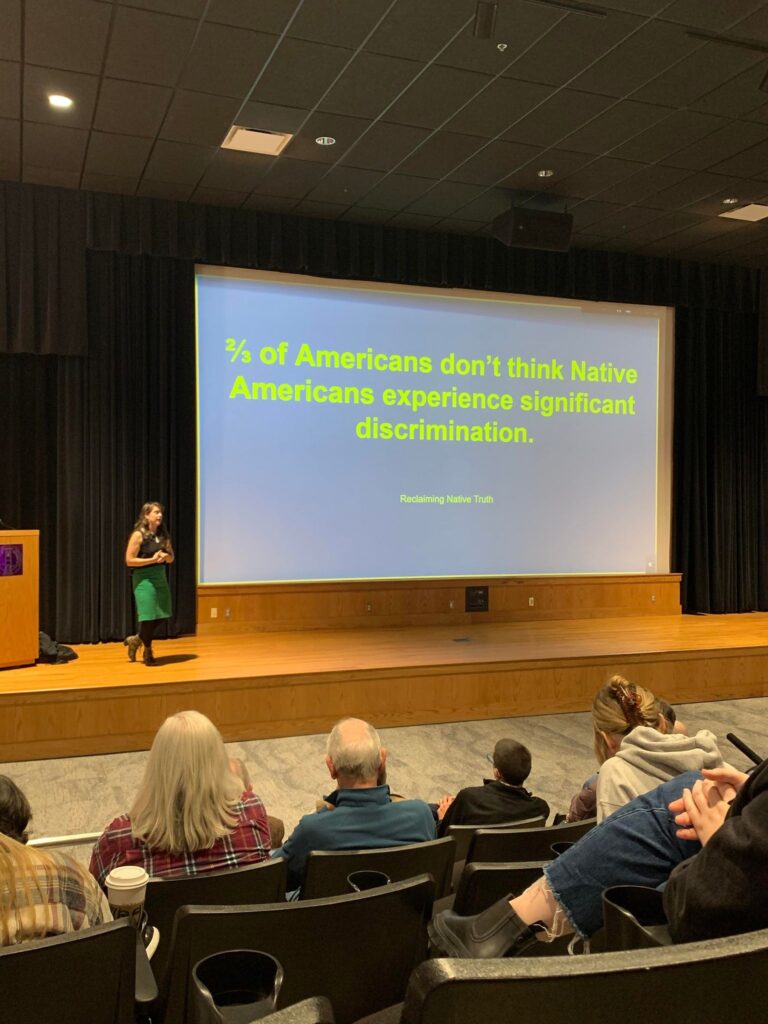

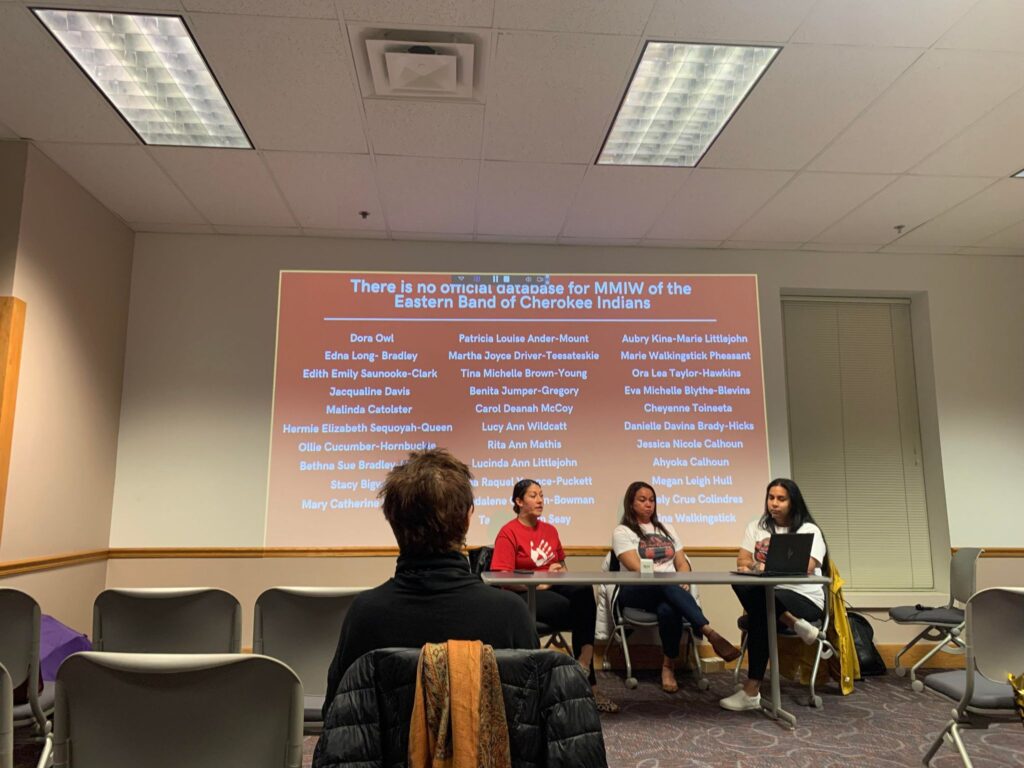

During their visit to WCU on Nov. 15, the women discussed at length the contributing factors to this silent epidemic. This includes conflicting jurisdictions between tribal, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. Along with the lack of a national database to record the number of MMIW cases, and the lack of care the media has shown reporting on the women – if covered at all.

Due to the overlap in jurisdictions, the FBI ends up handling a lot of the MMIW cases and according to the ‘We are Resilient’ crew, tends to only investigate the cases they deem of high importance. Typically not including domestic violence crimes.

“A lot of tribes are sovereign nations, which means they create their own laws. Which can be beneficial in some cases, however, regarding criminal cases it’s detrimental. Because then you have the state, the tribe, and any federal bureau of investigations involved in a lot of the cases,” said Ahli-sha Stephens.

If a crime is committed between two Native Americans, they can try the case in tribal court. But if a non-native person and a native person are involved, the tribe doesn’t have jurisdiction over non-natives so they can’t press charges. The case gets handed off to the FBI, and virtually nothing can be done against them.

The most recent report on the number of MMIW cases in the U.S. was completed in 2016 by the National Crime Information Center, reporting a total of 5,712. This number is predicted to be a severe undercount by the U.S. Department of the Interior Indian Affairs, due to the frequent misclassification of indigenous women’s race as Hispanic or Asian on missing-persons forms, and that thousands of cases have been left out of national missing person databases.

Through their research, the WAR cast has compiled a list of the 32 known MMIW cases within the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian tribe. 10 reportedly happened along the Qualla Boundary, 14 died from gunshot wounds, 7 are unsolved, and the victim’s ages range from 8 months to 54 years old.

“I had no idea that this epidemic was as big as it was until we dove into this project and it’s become our path I think. To bring awareness. We just hope that we can educate you guys and bring to light what’s really happening in indigenous country across America,” said Ahli-sha Stephens.

It’s said that when an indigenous woman dies, she dies twice. Once when her body dies, and another when she stops being talked about. There are national MMIW chapters where you can give time or monetary donations for the cause, but simply saying the women’s names helps a lot.

MMIW is widely regarded as a silent epidemic in native communities, and it will only stay that way if we don’t talk about it. Continue educating yourselves outside of Native American Heritage Month, and share your findings with others.