The first thing I saw when we reached Aida refugee camp was the face of a dead child.

Israel has been a topic of global discussion recently due to a resurgence in violence. After Israeli forces killed nine Palestinians in a refugee camp, a Palestinian opened fire outside a synagogue and killed seven Israelis. The Israeli government under Benjamin Netanyahu has cracked down on the West Bank with concerns of violence will escalating into a third Palestinian uprising. Hopes to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict peacefully seem further away than ever.

News of conflict in the region is not surprising after 70 years of violence and unrest. Although this conflict may seem distant from Cullowhee; it’s a little unsettling to one on-campus church group, the WCU Wesley Foundation, who visited the region in December. They have tried to bring their own perspective to the conflict and why it continues.

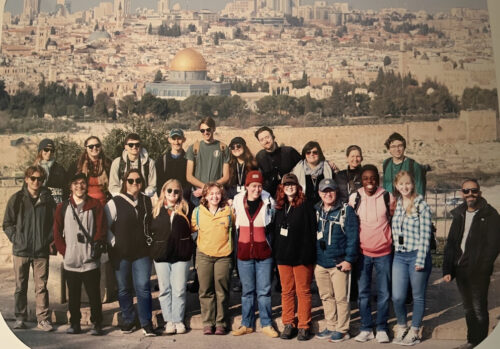

While the purpose of the trip was to see religious sites throughout the Holy Land, we also stopped in the Palestinian refugee camp Dec. 31. Our group consisting of 12 students, three Wesley staff members, the Wesley director’s family and two guests visited the camp as part of a tour led by local guide Deeb Dides. What we saw and learned at the camp would follow us back home to the States.

Established in 1950 near Jesus’s birthplace at Bethlehem, Aida Camp houses Palestinians removed from their homes in western Jerusalem and Hebron. While refugees were initially promised a speedy return to their homes, 5,500 people still live there today. The camp is partially surrounded by the Israeli separation wall and sees unemployment levels of 43%.

Dibes was surprised when the Wesley Foundation requested to visit the camp, according to Jay Hinton, campus minister and Wesley Foundation director.

“He said most groups don’t want to do that…” Hinton said. “They want to have an experience that reinforces the stuff they think they already believe…He was really pleased that our group was wanting to get educated on what’s happening over there.”

What we found left the students shocked and anxious. Upon entering the basement of the Aida Youth Center, we were immediately told that we’d entered the most tear-gassed location on Earth. The camp had been gassed the day before, and students began to sneeze shortly before we left because of the imperceptible fumes lingering throughout the building.

The Aida Youth Center occupies the entirety of its five-story building, featuring a small museum and gift shop. The entire camp covers less than 0.071 square kilometers and mostly consists of housing complexes separated by thin alleyways. The camp is within an afternoon’s drive of Jerusalem, Israel’s capital and largest city. The refugees can freely access the West Bank and small parts of the capital but are not allowed through the gate into West Jerusalem.

Near the end of the tour, we climbed to the roof of the Aida Youth Center and saw expended tear gas canisters. Moments later, we heard four sharp reports that sounded like gunshots. While many of us were frightened, the Aida representative didn’t elaborate. He said this was normal, but some of us began to fear for our lives.

The border wall that surrounds certain areas of the camp is tall, grey and spotted with guard towers but has since been covered in political and artistic graffiti. It reminded many in our group of pictures of the Berlin Wall dividing the East and West districts of Germany’s capital at the height of the Cold War, which has since been torn down.

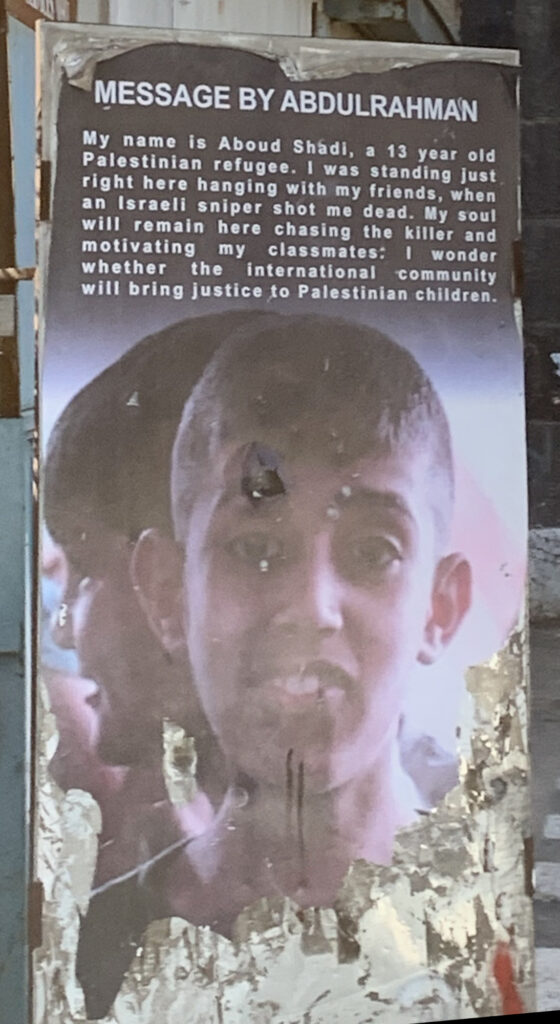

Due to their proximity to the border wall, Aida faces daily attacks and brutality from the Israel Defense Force—also know as the Israel Occupational Forces to refugees. We watched a video of children being chased off a basketball court by men in military uniforms. A board near the entrance marks the spot where Aboud Shadi, an innocent 13-year old refugee, was shot dead by an Israeli sniper.

“My soul will remain here chasing the killer and motivating my classmates. I wonder whether the international community will bring justice to Palestinian children,” reads the sign, whose words were credited to someone named Abdulrahman.

Shadi’s death shocked the Palestinian people, as never before had they been struck so suddenly at their front door during a peaceful day. There isn’t a legitimate reason for the attack, and Israel’s explanations were inconsistent and certainly insufficient. We couldn’t help but feel we had failed the young child who stared at us both as we were arriving at the camp and as we were leaving.

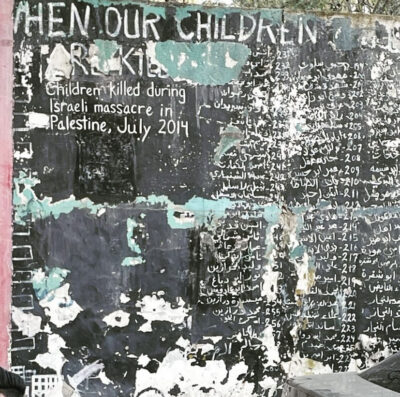

The camp itself is built of stone buildings and partially surrounded by the border wall, both covered in Palestinian artwork commemorating their homeland and honoring martyrs. Some of the art is original works by Bansky, the famous anonymous street artist. Outside the Youth Center is a list of over 200 children killed in a massacre July 2014.

“There’s something about human nature,” said Hayden King, a first-year Philosophy and Religion major. “That whenever you see violence or oppression or wrongdoing against children, it really hits you harder than some others, and just kinda shows how bad the situation is there.”

Central to the art is a picture of a brass key, prominently featured above the entrance to Aida. This represents the house keys passed down through generations of refugees, with the hope that they will one day use them again.

Aside from the art, there are few visible traces of resistance—aside from a single watch tower along the wall that had been burned out by Palestinian refugees some time ago. According to Hinton, there is something oddly sad about this lone symbol of success against their oppressors, which seems so small and insufficient to us.

“There’s towers all along that wall, right,” Hinton said, “And this one tower that’s been attacked and burned out and become inoperable…becomes this symbol of hope for them too.”

While many of the buildings are run down and their unpredictable water pipes are tiny, the camp remains surprisingly vibrant and permanent.

“I’ve never seen a refugee camp ever portrayed in any type of news media that was like where we were,” said Jennifer Hinton, Recreational Therapy professor at WCU. “It felt like I was standing in Brooklyn or something instead of tents and scoops of rice going out.”

The refugees have carved out a place for themselves in what they thought would be a temporary home. They have even found new uses for the weapons of their oppressors.

“Just around the corner from the place we were was a shop,” said Jay. “And part of their sign said they had jewelry and things that were made from expended tear gas canisters.”

The Aida Youth Center has taken the lead in empowering the camp’s youth to serve the local community. While at the center, we saw children running through the hallways and playing in the streets, yet it was hard not to fear for them after what we had seen.

“Listening to them talking about getting tear gassed while I could hear the children laughing in the hallway,” Jennifer said. “And being a mom and thinking about how desperate it would be to try to keep my children safe at all times…would cause me a lot of consternation.”

The modern history of the Holy Land is complicated, often defying simple explanation. The Aida representative emphasized that the Israel government and Palestine were not in a “conflict.” Palestinians call it a “nakba,” which suggests a prolonged disaster with the Israeli government as the primary aggressors.

The relationship between Israel and Palestine reminded us of the relationship between the U.S. government and Native American groups. The Israeli government was founded in the mid-1900s, with the goal of creating a home for the Jewish people in the Holy Land after World War II, when many Jewish people were systematically murdered in concentration camps. While the Bible promised this land to them, it was already inhabited by many ethnic groups, including Arab Palestinians. Religion was used to hide colonial aggression. Many of these Palestinians were moved from their homes to 61 refugee camps across Palestine.

“Every time I think of our home there [in Jerusalem], it comes to my mind that some strange person is literally living my life, knocking on my door, taking off my shoes, and enjoying the freedom that God’s supposed to have provided to us, for me,” the Aida Representative said. Though he seemed to be in his last twenties, his resigned expression seemed to come from generations of struggle.

King acknowledged the irony of the situation, saying “the oppressed had become the oppressors.”

We felt some guilt at coming all this way to visit a place that the people here weren’t allowed to enter.

“Our speaker that day…had never been to Jerusalem, which was five miles away,” Jennifer said. “And that I was just gonna like ‘la dee da’ my little American self wherever I wanted in Jerusalem that evening really bothered me.”

Of course, there’s two sides to every story. In the camp, we were repeatedly shown a map that seemed to demonstrate Palestine’s shrinking territory at the hands of the Israeli government. However, this map is misleading propaganda that ignores the complex history of the land’s ownership before Israel’s founding.

Additionally, while Israeli forces are no doubt responsible for the deaths of Palestinians, many Palestinian militant groups such as Hamas have killed innocent Israelis. However, it would be a mistake to equate such groups with the refugees, just as it is a mistake to equate the actions of Al-Qaeda with all Muslims.

In the same vein, Dides pointed out that many Israeli citizens do not support their government or its actions against the Palestinians. However, they feel powerless to stop the killings.

Students felt a similar sense of powerlessness upon returning from the trip to their homes thousands of miles away.

“I think it leaves you with that question of how do you help in some situation like that, because it’s so big and so complex and so long-lived…” Jennifer said. “You need to really find out what the people there need, and make sure that you’re helping them to do what they need to do…Sometimes the things that are most valuable to them are things that we don’t necessarily understand because we don’t live there.”

At the camp, we were told that coming from a privileged society, our most important tool was our voice.

“The thing that I feel like I received the most is a sense of duty,” King said. “I went there, I saw something that a lot of people haven’t, and I feel like it’s my job to talk about it…The only way it’s gonna be stopped is if more people know about it.”

Most of the students had no grasp of what was happening in Palestine prior to the trip, which can be intentional, as limiting information can contribute to the government’s power.

“What we see in the Western news is just a sliver, and it’s always whoever’s painting the picture.” Jennifer said.

Despite the hopelessness of the situation, King and other students in our group had hope that they could make a difference, however small, in their own community.

“I don’t know if I can change the government,” King said. “But I can change the people.”

See more photos from the camp below: