Don’t worry I heard it too! A mysterious whistle, similar to that of a steam train, has been heard howling within Western Carolina University.

This has some students wondering where the sound is coming from, and this railroad-enthusiast reporter digging for answers.

Take a walk around the university on a weekday and keep an ear out at noon. If you’re in the right area, you’ll hear what sounds like a train whistle sound off four times. What’s the deal? Is the “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” chugging around Cullowhee? Or are sleep-deprived students hearing things due to a late night of homework?

Don’t worry Catamounts. You’re not losing your marbles. With special access to university property and a compelling interview with a WCU official, yours truly headed to the one place on campus where steam is sure to be found. Not only will I shed some light on the whistle mystery but reveal a vibrant history.

Steam plays an important role at Western Carolina University. Unlike other up-to-date campuses that tend to use more modern tactics, WCU continues to operate a full-working steam plant which provides students with hot water and heat year-round. Located along Central Drive, the plant operates 24 hours a day, 365-days a year and requires employees present at all times. Overseeing this newly renovated old-fashioned operation is the plant’s supervisor Terry Riouff. A passionate historian with over 20 years of experience running the facility, Riouff confirmed that the whistle is coming from the plant. In fact, he is the one making sure it’s heard.

In late 2022 after renovations to the steam plant were complete, Riouff installed the whistle on the roof of the new building. Early this March, Riouff started sounding it four times every weekday at noon.

Much different from the old days, this process is mostly automated. Well, not all of it… Riouff must keep an eye on time as the whistle isn’t programmed to automatically go off. At noon, Riouff taps a button via computer screen and automatic valves channel steam to the whistle four times. Riouff was glad to escort me to the roof to capture the whistle in action.

Riouff says that this is not the first time the whistle has been heard in Cullowhee. Although it is unsure exactly when the whistle came to WCU, its days of service to the campus were spent on the old plant, built in 1923.

“Back in its heyday, the whistle was used to signify certain daily time changes on campus and the surrounding communities. The start of work, end of the workday, lunch time, and so-on. Few people had watches back in the day,” Riouff said.

A few questions still remain. Is this the only purpose the whistle has served? Or was it once traversing ancient railroad lines atop a genuine steam locomotive? Riouff has good news for railroad-buffs.

“From what I understand, it did come off of an old locomotive,” Riouff shared. “I’m just not sure when it first came to Western.”

The railroad played a vital role in the creation of the steam plant. The first boiler was delivered by the Southern Railroad to Sylva where it was then pulled by Oxen to campus. I asked what railroad company the whistle may have come from, but Riouff didn’t have an answer. Additionally, no railroad tracks are visible in Cullowhee. I had to dig further…

During my tour, I inspected the whistle closely for company engravings. Finding none, I reached out to Eli Griffin, a railroad conductor at the Dollywood Theme Park. With a unique ability to identify whistle manufacturers by sound, Griffin was able to point to the “Lonergan” company. However, Lonergan didn’t make whistles for major companies such as the Southern. This debunked an initial theory I had that it may have come from a Southern locomotive. Surely Cullowhee had a railroad at some point. I dug deeper, hoping to find a railroad presence closer to campus. After studying ancient topography maps from the Southern Appalachian Digital Collections, I struck gold. What I found was a small railroad line that once extended from Sylva to East Laport while passing through Cullowhee. It was privately owned and known as the “Tuckasegee and Southeastern” or “T&S” for short.

Abandoned in 1940 and removed in 1945, the T&S had connections to smaller logging lines that branched off from East Laport into the dense forestry of the region. These precarious lines used “Shay” and “Climax” locomotives which were gear-based and built for such tasks. Lonergan whistles were more commonly used on these lumber hauling workhorses. Although no final answer on the whistle’s exact origin is known, it’s safe to say it most likely came from one of the local logging lines which seems fitting to be in the university’s hands.

In 2017, after being removed when construction on the new facility began, the whistle was defunct and in disrepair. Thanks to voluntary efforts from an internship team, the WCU Rapid Center soon had the whistle back in working order. When the new plant was opened in late 2022, various residents and officials urged Riouff to re-attach the whistle to pay tribute to the past. Riouff was happy to oblige and started blowing the whistle early this March.

“When we installed it on the new plant, I took it upon myself to blow it every day at noon just like the old days,” Riouff said. “It seems a shame, the thought of having something like that from our original plant and not using it.”

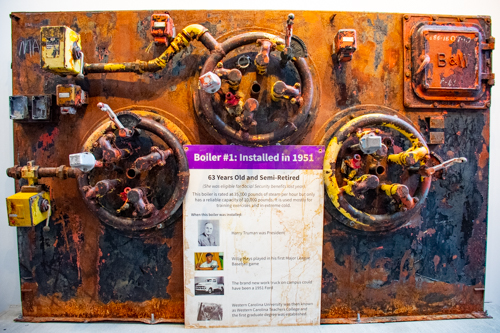

According to Riouff, the old plant was no easy task to keep running. It used coal as a fuel source and had one boiler at the time. Later, the plant was converted to operate off black oil with the addition of a second boiler. In 1969, a third boiler was installed, and a fourth and final arrived in 1974. With a “shelf life” of up to 20 years, these boilers stood the test of time due to the critical care of employees. Respectively, boiler two lasted as long as this past January. Although the new boilers replaced most traces of the originals, the first boiler’s “burner front” is on display in the new plant.

The most notable improvements of the revamped plant are newer, more efficient boilers with increased redundancy. This allows the luxury of backup systems and pumps in case a problem arises. Additionally, an easy-to-use computer system has replaced much of the methods used to light the burners. The new plant also comes with a lab for collecting and analyzing water samples to ensure the steam being produced is clean and safe. Amidst the upgrades, Riouff is proud that the plant continues to utilize steam and has no hesitancy saying so.

“Steam is a lot more efficient than electricity or a hot water system,” Riouff said. “You don’t have to pump steam”.

With many buildings on campus being upgraded, completely new, or fully demolished like the old “Scott” and “Walker” dorms, it seems hard to find a substantial amount of history in Catamount Country. Nonetheless, thanks to the efforts of preservationists like Terry Riouff, rest assure that a little campus history can still be found for as long as the whistle wails.