After many decades, humans are exploring the stars again, and one WCU professor got the chance of a lifetime to help them reach the Moon again!

Dr. Amy Fagan is a geology professor who also teaches astronomy courses. It’s clear from the LEGO lunar lander on her desk that her interest in the project goes beyond the professional. Space travel is an exciting topic for her. Fagan uses her knowledge of geology to study Apollo moon rocks and lunar meteorites and even serves as chair of NASA’s Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG).

Her astronomy class regularly devotes a full week to the Moon and lunar missions, so playing even a small part in one has been a dream for her. She got her chance when she assisted with a moonwalking test mission in October.

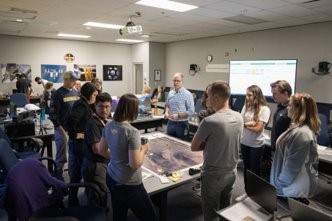

The Joint EVA Test Team #3 (JETT3) was a dry run for the actual moonwalk of Artemis III, conducted in similar conditions. Fagan was not actually walking through the Arizona desert in a space suit—that job went to the two astronauts, Andrew Feustel and Zena Cardman. Fagan was in the science evaluation room in Houston making decisions based on the data collected and communicating with the astronauts. She also worked for months before the event, plotting the best places for the astronauts to collect samples at.

In addition to testing the astronauts’ ability to navigate and collect data in their suits, the mission tested the protocol and design of the evaluation room. Overall, NASA’s team was learning to get the most information they could in a short time at an unfamiliar landscape. Each step taken to prepare for the mission in Arizona would be replicated for the landing site on the Moon, accounting for the unique features of both regions.

The JETT3 Process

The test ran from May to October, although the main event only took one day.

“In the late spring and all through the summer, we were performing…all the tasks that need to be done before a mission,” Fagan said. “So, this whole JETT3 activity was a simulation of Artemis III.”

While this work wasn’t as glamorous, it was incredibly important. Walking on the Moon is a once in a lifetime opportunity, and the astronauts have limited time. The months spent planning their route allow NASA to get the most valuable information and make the most of their exploration.

JETT3 prepared scientists in NASA for the decisions they’ve have to make in the lead-up to Artemis III.

“When we have Artemis III,” Fagan said. “Somebody has to decide where the crew is gonna walk on the surface…Somebody has to decide ‘Oh, the crew is gonna walk this direction, this far, they’re gonna stop at this big boulder and collect a sample…They’re going to dig a trench or take a core of the materials.’ So that’s a group of scientists and engineers who do that! That was what we were doing over the summer.”

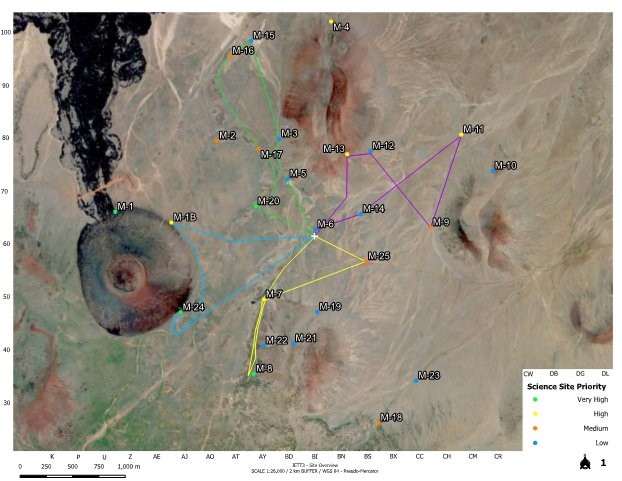

Fagan wasn’t the one plotting this course, but she did decide the locations the astronauts should visit. A separate team looked at the slope of the landscape to decide how they would navigate between them in the shortest possible time. Some locations would have to be skipped if there was no easy way to reach them.

When a similar team prepares for Artemis III, they’ll be looking at the South Pole of the Moon, an area that humans have never touched down on before. They’ll work with telescope photographs of the landscape to decide on the most important locations to collect data at.

For JETT3, scientists were simulating a landing on Arizona. Obviously, humans had been there many times before (including several members of the team), but the scientists had to pretend they hadn’t. Fagan pointed out that while an object on the map might obviously be a volcano, her team had to pretend to know nothing about it and instead consider how they could learn more about the structure.

The team also tried to replicate conditions on the Moon for the actual moonwalk. The South Pole of the Moon receives very little sunlight, so the test had to be done at night.

“The lighting conditions are gonna be very extreme,” Fagan said. “Very long shadows. There are times where it’ll go days without any sunlight in a particular area.”

To prepare the astronauts for these conditions, the crew in Arizona worked in the dark with lights on their suits to guide them. An artificial Sun (a fancy term for a big light) simulated the long shadows caused by the sunlight. The science team had to work at the same time—from about 7 p.m. to 3 a.m. in a windowless room in Houston.

The team limited their information to what the Artemis III team would work with. Rather than using high-resolution Google Maps images, they stuck with pictures of a similar quality to images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a robotic spacecraft which orbits the Moon and maps its surface.

“We had to look at that location,” Fagan said. “And say what are some of the science objectives that we think we could achieve at that landing site.”

Of course, the science objectives weren’t the point of the test. The team wasn’t likely to learn anything about Arizona that they didn’t already know. What was being tested was NASA’s ability to collect data that could be used to draw such conclusions—and to respond to unexpected changes in their plans.

“As part of the science evaluation team, we had to make changes during the mission of ‘okay, we are spending too much time doing this task, we’re gonna have to drop another task.’ So, we were constantly evolving the plan and dropping things off because it was taking longer to do certain things than we were anticipating,” Fagan said.

For Artemis III, the crew will spend about six and a half days on the Moon, much longer than previous missions. However, much of this time will be inside the Starship lander. Their moonwalks will be much shorter, requiring on-the-spot collaboration with the team in Houston.

NASA was evaluating the functionality of the science team, how tasks would be split up between them, and even how the room they were working in should be set up. From where people set up their workspaces to how many screens to have in the room, there were a lot of factors to consider.

In order to get complete information, team members even swapped roles in the middle of the test. Fagan started as the tectonics lead for the first two activities and then kept track of all the samples that were collected for the last two.

“It gave a lot of interesting results that I think are gonna help when Artemis III is being developed,” Fagan said. “Because now we’ve done a test where you have crew going out into the field, trying to do geologic activities, and they can’t see very well. How is it that you try to direct them where they’re supposed to go?”

While it may seem a little silly to have some of the most distinguished scientists pretend to explore Arizona, these tests are vital to the process. While space travel seems exciting and fun, it’s also very dangerous. Many missions have ended in tragedy or failure, even those that took place on the ground. Running multiple tests takes a long time, but it ensures the most important missions will go as smoothy as possible.

A new generation of Moon landings

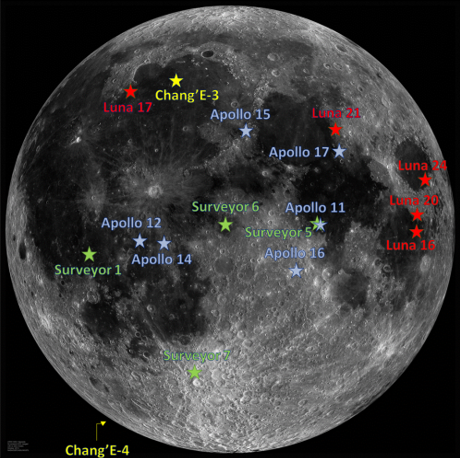

U.S. astronauts first landed on the Moon in the context of a diplomatic war with the Soviet Union (now Russia). Your average U.S. citizen cared less for what would actually be found on the Moon than they did for beating the Russians there. As a result, the first lunar missions were conducted in a frenzy under the excited eyes of the public, but NASA still took every step they could to reach the Moon as safely as possible.

NASA began its bid to win the space race with the Mercury and Gemini missions, which carried one and two-astronaut teams beyond Earth’s atmosphere. However, by this point the Soviet Union had already launched the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into space, so NASA quickly moved on to the three-astronaut Apollo missions.

The United States won the space race with the Apollo 11 mission, landing the first astronauts on the Moon July 20, 1969. This was followed up with six more missions, landing 10 more Americans on the Moon—all men. One of these astronauts, Charlie Duke (who flew in Apollo 16), visited WCU Sept 11, 2019, speaking about his experience and desire to see more lunar missions. However, the public’s interest in Moon landings had faded considerably since the initial landing.

NASA announced the Artemis program on May 14, 2019, nearly 50 years after the last Moon landing. As part of this program, NASA plans to land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, but Artemis’s goals have an even broader scope than that. The program will establish the first long-term presence on the Moon and develop the technology to send humans to Mars.

In collaboration with commercial and international partners, NASA will create new infrastructure to allow for yearly Moon landings. The Gateway will be a space station orbiting the Moon that will serve as a pit stop for astronauts on their journey. The Artemis Base Camp will allow astronauts to live and work on the Moon with a lunar cabin, rover, and mobile home.

Like the Apollo missions, the Artemis program will occur in stages. Artemis I was successfully completed Dec 11, 2022. It was an uncrewed flight test of the rocket and space craft that will bring astronauts to the lunar surface.

Artemis II will bring a crewed spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth and is projected to occur in Nov 2024. NASA announced the crew Tuesday, April 4. The team consists of American and Canadian astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Hammock Koch, and Jeremy Hansen.

Artemis III will finally land two astronauts on the Moon’s unexplored South Pole. While it’s scheduled for launch in December 2025, delays are possible due to the difficulty of fine-tuning space travel.

Next steps for Fagan

NASA put out the call for Artemis III’s geological team in January, inviting individuals to submit proposals explaining their skills, knowledge, and experience to show why they belong on NASA’s team—like a job application. Fagan’s involvement in JETT3 began when she submitted a similar proposal in February, 2022.

10 proposals were accepted out of the 30 submitted. The proposals are evaluated by a review panel who choose a group for the mission. NASA doesn’t always select the top team—sometimes someone farther down might have a specific skill-set that makes them more valuable.

In the Apollo program, scientists proposed individually. This meant if two scientists didn’t get along well, they had to settle their differences on their own. For Artemis, NASA is having scientists propose as teams, to ensure that the final group can work together harmoniously.

Fagan plans to submit a proposal for Artemis III and hopes to be involved with the program in the future. The chances of not getting selected are significantly higher than getting selected, but Fagan could still get involved as a participating scientist, who serves in a support role outside of the science team.

“Right now, the lunar community is not sleeping very much, because they’re trying to get those proposals in soon,” Fagan said.

Whatever her future involvement may be, Fagan mainly wants her students to know that lunar missions are not ancient history.

“We’re going back,” she said. “There’s still a lot of people who don’t know about Artemis…It’s moving very fast now, it’s really happening, and I want people to know that we’re going back!”