Originally published in the Western Carolinian

“Micro-aggressions, even though they’re small, when you deal with them a lot of times throughout your life, they become bigger issues.”

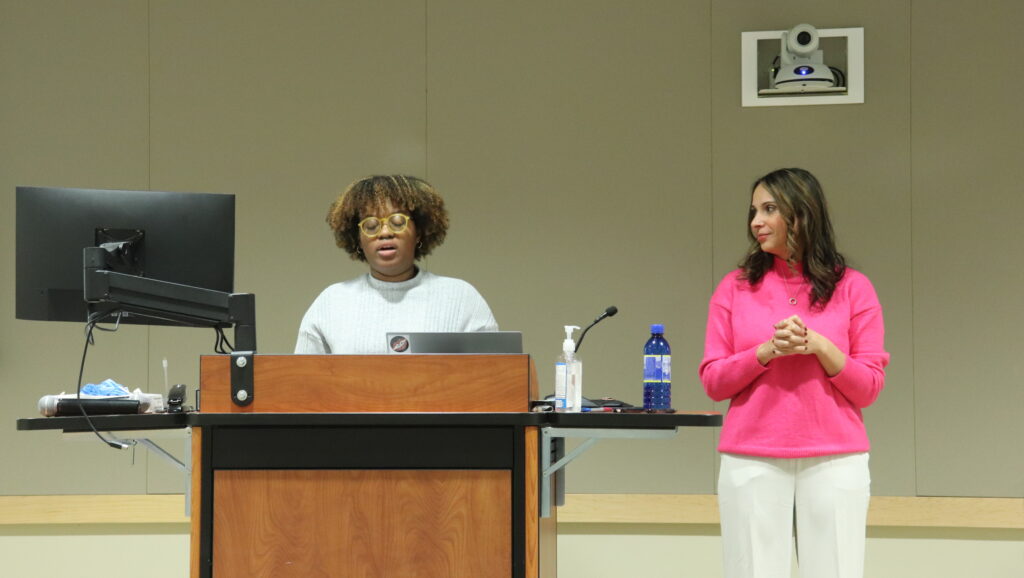

Nursing student JammyLee Saintons and nursing professor Dr. Mariana Da Costa taught students the importance of understanding micro-aggressions during their event “Making the Invisible Visible: Let’s Talk about Micro-Aggressions” on Feb. 13 in HHS. With the partnership of the Association of Nursing Students (ANS) and Intercultural Affairs (ICA), the two presented the impacts and how we can recognize our own actions.

For those that are not familiar with ANS, Da Costa explained, “The Association of Nursing Students is linked to a bigger national association, and it’s aimed at really supporting nursing students in leadership efforts. Our group specifically focuses on community outreach and leadership development.”

During the lecture, Saintons and Da Costa explained how micro-aggressions can be unintentional and may not be seen at first. Many people may exhibit them without noticing or understanding why they are wrong. Over time, this can cause depression, development of coping strategies, racism battle fatigue, and suicide. “Suicide is the easiest death to avoid… there are higher suicide rates for young [people of color],” said Dr. Da Costa.

One of the ways we can see our own biases is through the Harvard Implicit Self-Assessment where you are tested on or beliefs about certain topics and given some information about yourself. Other ways discussed during the lecture are to be open-minded, open to conversation, work to educate yourself and not to be defensive when your actions are pointed out.

“For us to have change, we need to make the uncomfortable comfortable. We do have those uncomfortable conversations, but we don’t talk. The more it lingers, the more it doesn’t get exposed… But if we don’t talk about it, then we won’t be more aware,” explained Sainton.

Examples of micro-aggressions

Saintons gave examples of micro-aggressions in different situations that came from anonymous sources.

“A microaggression I faced recently [was] where someone told me that I should spend more time flipping burgers instead of getting a job that was essentially out of my league. I had asked him why and he stated that ‘Everyone needs to start somewhere.’”

“… when people get upset that queer people “make it their whole personality” when really, it’s just who we are…when really, it’s not my personality, it’s a form of self-expression and it wouldn’t have really bothered them if they didn’t have a problem with me being queer.”

What students should know

“Ideally it’s just having an awareness. I think that’s where it all begins,” said Da Costa. “Just understanding what they are, the fact that they are detrimental, and just being aware of some of the themes and things that will fall under that category of a microaggression.”

Saintons wants students who missed the lecture to know that you can avoid committing microaggressions by being aware of what you are saying and being open to hard conversations.

“Don’t be so defensive if someone tells you what you say could be offensive because micro-aggressions are unintentional or unconscious. You may not know what you’re saying is wrong because you’ve never had someone tell you what’s wrong… because you may not have been exposed to those types of communities…ignorance is not your friend,” Saintons said.