Story co-produced with Daniel Reid

When people think of veterans, they think of people like Tom Baker. Yet combat trauma does not discriminate based on age.

Austin Summers is a 25-year-old combat veteran. He served in Afghanistan for roughly six months and lost three of his friends.

Austin enlisted in October 2016 and shipped out in January 2017. He worked as 91B wheeled vehicle mechanic during his time in the Army.

Injuries are expected in the military and not unusual. Often the solders choose to not seek medical assistance. Austin broke his pinky and both big toes while deployed in Afghanistan and as a paratrooper he had his fair share of scares when hitting the ground.

After one jump, Austin thought he had broken his back due to how hard he hit the ground.

“I had a jump in October of 2018, a normal day, it was a little windy,” Austin said. “I’ll never forget I hit the ground like a bag of potatoes. I smacked it as hard as I’ve ever smacked it. It knocked the wind out of me. 100% thought I broke my back.”

He described the pain as excruciating and was not able to bend over at all which endured for weeks.

There is a negative attitude toward seeking medical treatment in the military out of fear of being seen as, what some members like to call it, a sick-bay-commando. This negative outlook deterred Austin from seeking medical treatment and he chose to stick it out.

Physical injuries are just as common as the mental scars that military members endure.

During his deployment to Afghanistan, he was part of a ground unit ODA, operational detachment alpha, of Green Berets. He was part of this group for 6 months.

Austin witnessed his first losses while in Kunduz, Afghanistan fighting against the Taliban.

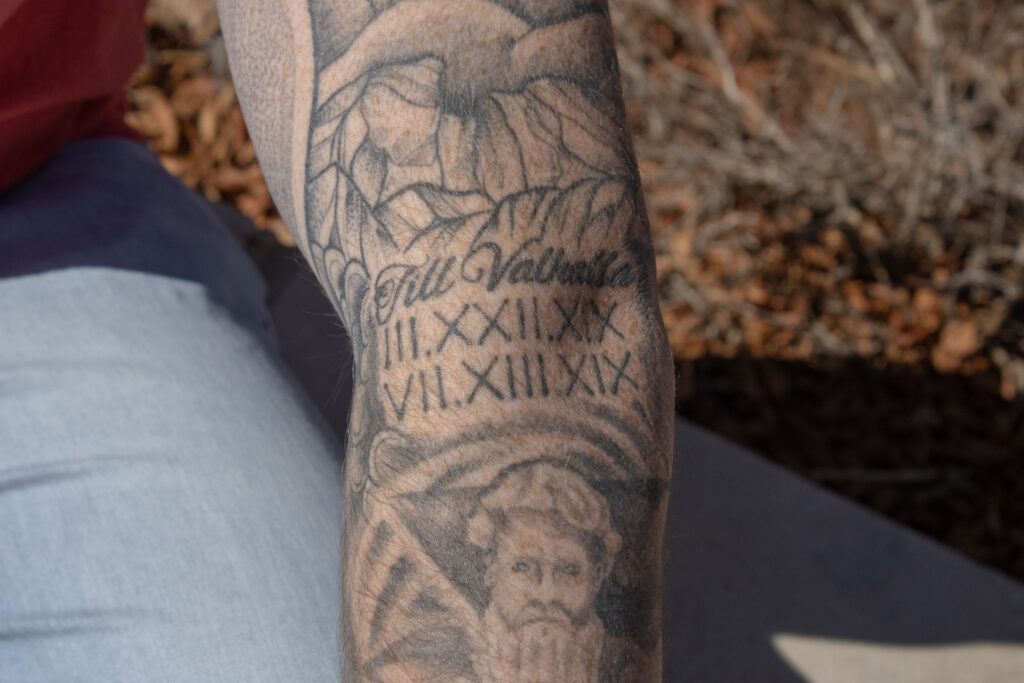

SFC Will Lindsay and Sgt. Joseph Collette had sprinted around a corner while taking fire and both received fatal wounds. They died next to each other in Kunduz, Afghanistan March 22, 2019.

Austin witnessed their deaths through the ISR footage of the drone accompanying them. It took them 45 minutes to reach Lindsay and Collette.

On a mission in North Western Afghanistan traveling between Maymana to Mazar-i-Sharif the convoy Austin was in encountered three IEDs. The first two hit Afghan vehicles that were accompanying them and the third hit two vehicles in front of the vehicle Austin was in.

Austin maneuvered his vehicle into a recovery position to aid other members that had been hit by the third IED while the Taliban ambushed the convoy. They waited until nightfall before they were able to move the convoy back to the base.

“After we hit that third IED I was like yeah, we’re not making it home,” Austin remembers. “We were just going to keep hitting them and it was just going to keep happening.”

A week before his last mission Austin mounted a mini gun on one of the vehicles in his convoy. The armor shield that is normally mounted over the gun was left off because it did not fit over the mini gun.

On his last mission in Afghanistan, Austin and his unit traveled along the same route they hit the three IEDs. Sgt. Major James “Ryan” Sartor opted to man the mini gun in the convoy during this mission.

Sgt. M. Ryan was in the Army for 19 years with this being his last deployment before he separated from the Army. He had four kids and a wife state-side he was ready to go home to.

That was the last mission he ever went on.

Austin started spiraling once he got back to North Carolina in 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic hit. He turned to alcohol to cope with the traumas he endured while in Afghanistan.

“I got to the point where I was drinking til I was blacking out pretty much every time for about three months,” Austin said.

He started realizing that he needed to slow down when he would wake up with pain from his liver.

“I didn’t realize I was drinking to cover up a lot of the thoughts I had and trauma that I went through and not really processed,” he said. “When you’re overseas you don’t have time to process.”

It took one of his buddies, Noah, who had also served in Afghanistan to tell him that he had a problem and that he needed to seek help.

“I didn’t want to admit that I needed help,” Austin said.

Noah and his mom convinced him to seek help through the VA in Asheville.

He would go off and on for about two to three months and would think he was better and stop going. Two or three months would pass and he would start having issues again.

It was an endless cycle.

In the fall of 2021, the reactions to the unprocessed trauma started to manifest more. While attending the funeral of his girlfriend’s grandmother, bagpipes started playing and triggered a panic attack.

“I started hyperventilating I wasn’t able to breath, I didn’t know what was going on,” Austin said. “I just kept on saying ‘I’m scared, I’m scared, I’m scared.’ I didn’t know what to say, that is all I could say.”

One of the family members that attended the service served in Iraq and related to Austin saying that they get to him as well and that he should see someone and talk about it. Austin didn’t think much of it at the time.

Two months after this incident he was walking on campus when someone started playing bagpipes near the fountain.

“I got to where Hillside Grind is and I just paused,” Austin said. “I covered my ears and started humming.”

He broke down to his professor the same way he did at the funeral. The professor escorted him to CAPS, and he realized he needed more help.

He started attending therapy through the VA consistently and was diagnosed with panic disorder, generalized anxiety and depression. He was not able to find a medication regiment that helped.

He went to the trauma center in Asheville as a last resort. He went through the process of EMDR, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, which is a psychotherapy treatment meant to help with trauma.

He sat in the office with a physician moving their fingers in front of his face and was told to recount what he went through while following the physician’s hand with his eyes.

“Each session I would go through a different experience from Afghanistan, and I would have full mental breakdowns,” Austin said. “I would be able to smell the way things smelled over there. I would remember little things that normally people wouldn’t remember.”

These sessions helped him process his entire deployment and come to terms with his trauma and not compare it to other people and think he didn’t have it as bad as someone else. It is his trauma and it’s his to bear.

Summers was formally diagnosed with depression, general anxiety disorder, and panic disorder; with post-traumatic stress disorder being the overarching cause.

He manages the side effects of his trauma through smaller things that he is able to control. He always sits at the back of the classroom, he always has to drive, and he is always hyper-aware of trash bags on the side of the road. These are things that will stay with him.

Austin arrived at Western Carolina University in August 2020, in the wake of his transition from military to civilian life. During his junior year, a fellow veteran introduced him to the Student Veterans Association, where he found a sense of community that he had been missing.

“There is this understanding between all of us of what the military is,” Austin said. “There is a language that is shared between us. There is this itch that my other friends at college don’t understand that these guys do.”

In an unexpected turn of events, the residing president of SVA left WCU, leaving Austin to inherit the position for the fall 2023 semester. Austin quickly established connections with various student veterans and filled out the club’s board; revitalizing it from what was previously a skeleton crew.

The brotherhood that has been created on campus by Austin and the Student Veteran Association reflects that of the military. There is a community that supports one another, that shares similar experiences.

Austin graduated from WCU on Dec. 16, 2023, with a B.S. in Criminal Justice and Emergency Disaster Management. He plans to attend Georgetown University in the spring of 2024 to earn a master’s in security studies in intelligence and terrorism.